It’s pointless to look for a fixed definition of “popular football.” It takes shape step by step, built from a wealth of alternative experiences standing against modern football. Somewhere between resistance and social transformation lies the glimpse of another kind of game, freed from money, commodification, individualism, and private ownership. Let’s talk about a revolution.

People have certainly tried to change football before. The social history of the game is full of utopians who claimed they wanted to “give football back to the footballers”. Long before Platini recycled the slogan for electoral purposes during his 2007 UEFA presidential run, it had been hung from the balcony of the French FA headquarters, occupied in May ’68 by a handful of rebellious players. Linked to the left-wing newspaper Le Miroir du Football, the protesters were already demanding an end to the authoritarian leadership structures of the time, symbolized by the “lifetime contract” system, abolished in 1969.

This spirit lived on within the Mouvement Football Progrès and its laboratory at Stade Lamballais, advocates of self-management and the 4-2-4 formation. From this emblematic 1970s experiment, the ambition to reclaim football remains alive – especially against today’s aggressive version of the game, the end result of the liberal turn of the 1990s. The only real limits the football-business machine – driven by FIFA and UEFA – will meet are those set by fans. From the terraces to alternative clubs, resistance takes many forms. The call for “popular football” has rarely felt so relevant.

From disgust to the underground

Disconnected businessmen and investment funds with no emotional tie to clubs only deepen supporters’ sense of dispossession, reducing them to mere customers. The disgust provoked by what’s now called modern football—and by the triumphant bourgeoisie running it—is impossible to overlook. It’s one of the breeding grounds for this football “for the people and by the people.” Rising ticket prices, TV-dictated kick-off times, exhausting collective sanctions, toxic owners, and endless scandals have pushed some to look for another way.

This is how Centro Storico Lebowski explained their founding: “We were tired of leagues without surprises, standings shaped by TV rights and palace intrigue, matches every three days – more frantic, less spectacular – a football with no waiting, no pauses, that can’t even hold out until Sunday; tired of obeying market laws that turn the game into a commodity; tired of a State that issues special decrees just to protect the business.”

This is how Centro Storico Lebowski explained their founding: “We were tired of leagues without surprises, standings shaped by TV rights and palace intrigue, matches every three days – more frantic, less spectacular – a football with no waiting, no pauses, that can’t even hold out until Sunday; tired of obeying market laws that turn the game into a commodity; tired of a State that issues special decrees just to protect the business.”

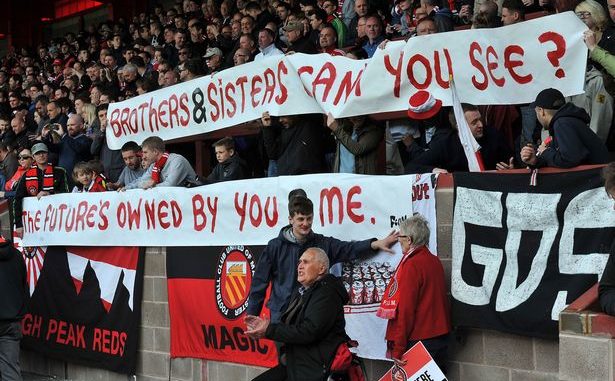

Before creating FC United, Manchester United supporters had staged several revolts against rising ticket prices at Old Trafford or against mandatory seating. The Glazer takeover was the breaking point. Setting up a “protest club” became the natural next step. In the 21st century, more and more fans are choosing this route. Creating one’s own club is a way to escape modern football – and to fight it more effectively. These new teams become small strongholds of resistance.

Turning clubs into commons

To grasp the scale of the phenomenon, you have to look beyond France. Whether it’s accionariado popular in Spain, fan-owned clubs in England, calcio popolare in Italy, self-managed teams in Greece, or alternative football in Indonesia, all share the belief that clubs should be common goods and common spaces – understood, in Silvia Federici’s sense, as forms of collective organization outside market logic. FC United’s slogan, “Our club, our rules,” sums it up well.

The principle of “one member, one vote,” transparent finances, and social engagement are the hallmarks of this other football – feminist and anti-fascist – thriving mainly at the amateur level. CFC Clapton in England, CS Lebowski in Italy, UC Ceares in Spain, FC Rainfall in Indonesia, NK Zagreb 041 in Croatia, Asteras Exarcheion in Greece, and PAC Omonia 29M in Cyprus are some of the emblematic examples of this experimental field of emancipated football, which still hits the glass ceiling of professionalism.

The principle of “one member, one vote,” transparent finances, and social engagement are the hallmarks of this other football – feminist and anti-fascist – thriving mainly at the amateur level. CFC Clapton in England, CS Lebowski in Italy, UC Ceares in Spain, FC Rainfall in Indonesia, NK Zagreb 041 in Croatia, Asteras Exarcheion in Greece, and PAC Omonia 29M in Cyprus are some of the emblematic examples of this experimental field of emancipated football, which still hits the glass ceiling of professionalism.

Often, these collectives extend their work far beyond sport. Deeply rooted in their neighborhoods and engaged with their communities, they position themselves as local actors. This can mean supporting strikes and mutual-aid funds, organizing food-bank drives, or working on gambling-prevention initiatives. Football is also a tool of solidarity: free academies for disadvantaged youth and projects supporting undocumented exiles.

All power to the socios!

For Bill Shankly, a club rested on a “holy trinity”: players, the manager, and supporters. He added: “Directors have nothing to do with it; they’re just there to sign the cheques.” The golden chapters of football were written by the children of the working class – of factories, mines, fields, and impoverished neighborhoods – and the sport has always carried this social tension. And Jock Stein’s famous line, “Football without fans is nothing,” remains a cornerstone of the popular approach.

Even as criticism of modern football grows sharper, questioning the privatization of clubs barely registers. In many places, reclaiming one’s club simply isn’t considered. It’s the symptom of a sport built on a rigid division of roles: players play, supporters support, directors direct. Even the supposedly participatory socios model in Hispanic countries has never stopped powerful notables from running clubs like the capitalist entertainment multinationals they’ve become.

Even as criticism of modern football grows sharper, questioning the privatization of clubs barely registers. In many places, reclaiming one’s club simply isn’t considered. It’s the symptom of a sport built on a rigid division of roles: players play, supporters support, directors direct. Even the supposedly participatory socios model in Hispanic countries has never stopped powerful notables from running clubs like the capitalist entertainment multinationals they’ve become.

Changing this is one of the challenges of the coming years. Talking about popular football means organizing hic et nunc to reclaim the game from below; to shift from use-based ownership to direct, collective management of our clubs. Not to “manage things better,” but to correct an injustice. This communist ideal can grow only on the ruins of modern football and the capitalist society that produced it and feeds it every day.

Leave a Reply